The migraine headaches began during an abusive marriage 16 years ago. The pain kept Christine bedridden for a week at a time and a doctor prescribed Vicodin – three pills a day. The headaches subsided, the stressful marriage ended, and she no longer needed the opioid pills for pain relief.

But Christine continued taking the pills and eventually three a day were not enough. She had developed an opioid use disorder.

“It gets out of hand and you don’t even realize it’s getting there,” says Christine, 50, of Fresno, who asked to be identified by only her first name because she does not want her employer to know of her drug use history.

Over the years, Christine tried to stop taking opioids, mostly at times when she could not fill a prescription or buy drugs off the street. Withdrawals – even the thought of having body aches, sweats, chills, runny nose, watery eyes, throbbing headache – drove her to take more pills. She went to an addiction clinic for help and quit for about a year but relapsed. While living with a friend out of state in 2020, she never took a pill but when she returned to Fresno and to familiar stresses, the drug use resumed. “A lot of it has to do with family,” she says. I’d try anything to escape that reality.”

This spring, Christine reached a breaking point and knew she had to get help. “I couldn’t take it here anymore. And so many times I had just thought about blowing my brains out, but I always pictured my kids at my funeral and that always stopped me. So, I knew I would never do that.”

She went to an addiction clinic, but it was on a Friday afternoon at closing time, and she was sent to Community Regional Medical Center (CRMC), where UCSF Fresno emergency physicians have a BRIDGE program to help opioid use disorder patients who are in crisis. Patients also can receive ongoing, follow up care at a new Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) clinic established by the UCSF Fresno Department of Family and Community Medicine at United Health Centers of the San Joaquin Valley (UHC) in Parlier. BRIDGE and MAT are among UCSF Fresno efforts to increase access to care and improve treatment for patients with opioid use disorder.

Opioid use disorder is at epidemic levels across the country and overdose deaths are increasing. According to recently released data from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 93,000 people in the U.S. died last year of a drug overdose, an increase of nearly 30% from 2019.

Substance use disorder, and in particular opioid use disorder, has increased in Fresno County during the pandemic, says John Zweifler, MD, a volunteer clinical professor at UCSF Fresno who supervises residents in the Family Health Care Network primary care clinic in downtown Fresno. According to the Fresno County Department of Public Health, 33 people died from the opioid Fentanyl in 2020, compared to 15 fatal overdoses reported in 2019 and only two in 2018. All opioids (including Fentanyl) led to 48 deaths in the county in 2019. Dr. Zweifler, a medical consultant for the Fresno County Department of Public Health, is working with UCSF Fresno Family and Community Medicine physicians to design an MAT pilot project for providing care to homeless individuals. “UCSF Fresno has a number of strong advocates for Medication Assisted Treatment,” he says.

“Access to treatment has to be easier than access to street drugs and until that happens, we’re going to have an opioid epidemic,” says Rais Vohra, a UCSF Fresno emergency physician, director of local poison control and interim Fresno County Public Health officer. Dr. Vohra helped establish BRIDGE at CRMC, which provides a link between emergency care and substance use disorder recovery programs. Patients are given buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist that works to decrease withdrawal symptoms and reduce physical dependence on opioids. The program, funded by federal and state grants, also has trained substance use navigators at CRMC who provide patients with referrals for ongoing MAT and links to other services.

“We are ready to serve patients 24/7 through the emergency department and see that there is follow up with a primary care doctor,” Vohra says.

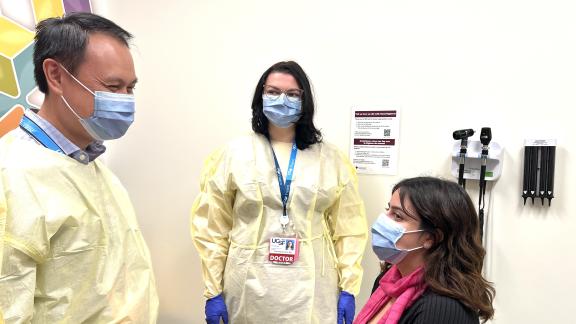

Christine received a two-week supply of Suboxone (a combination of buprenorphine and the overdose-reversing drug naloxone). She was given a referral for an appointment with Muhammad Shoaib Khan, MD, a UCSF Fresno Family and Community Medicine physician and addiction specialist who started the Medication Assisted Treatment clinic at UHC.

The prescription for Suboxone was a lifesaver, Christine says. The minute she put it under her tongue, she immediately felt like a “normal” person. “There’s no high to it. There’s none of that. You just feel normal.” And Christine, says, “that normal feeling is the best feeling in the world.”

But staying “normal” is a struggle. “When you feel normal, you also have to deal with reality. That comes along with it,” Christine says. Her twice monthly appointments with Dr. Khan and the appointments with a behavioral therapist that Dr. Khan arranged for her are essential to her recovery.

“Dr. Khan is very understanding,” Christine says. “He listens. He just sits there and watches you while you’re talking. So, you know he’s listening. He’s never rushed. Whatever time you need. He’s listening. He hears you.”

A lot of his MAT clinic patients have diseases that are stress related, Dr. Khan says. “Unless you take a multi-specialty, multi-modal approach to treating addiction, it is not completely resolved by taking a medicine. It is a psychiatric illness that needs to be addressed at the root cause. A lot of these folks who have substance use disorder are not taking the medicine to just feel a certain way, they are taking it because they have issues in their lives that they have not addressed and it’s a distraction. It is to cope with their problems.”

But there are various reasons for the overuse of opioids and for becoming dependent on them, Dr. Khan says. Some patients have ongoing physical pain that has not been addressed surgically or in other ways. Other patients have become chronically dependent on painkillers that were prescribed by physicians following a surgery or another medical condition. “We know now in addiction medicine that these folks don’t have the motivation to get off these drugs. So, you have to walk with them while they are on this journey of getting off these drugs. They are so dangerous that pain actually can increase while they are taking them. So, it’s a constant cycle where they take them for a long time, they feel more pain, they increase the dose, and it moves closer and closer to death.”

It is not a moral failing to have an opioid use disorder, says Liana Milanes, MD, associate program director and chair of the Behavioral Science Curriculum at the UCSF Fresno Department of Family and Community Medicine. “It’s easy to fall into judgment when it comes to addiction,” she says. “They need medicine just like the person with diabetes needs medicine. There is nothing this person has done really wrong. They have fallen into this chronic disease and now it’s something they have to deal with for life. The science behind addiction is that it is a chronic brain disease that is prone to relapse.”

Training physicians to be able to provide MAT is a priority of Drs. Milanes and Khan. This summer, they organized a Continuing Medical Education webinar for primary care physicians in the central San Joaquin Valley to teach MAT basics so physicians will not be hesitant of prescribing buprenorphine for treating opioid use disorder, be able to prescribe it appropriately; and also to have conversations with patients to decide if it’s an opioid use disorder, Dr. Milanes says.

In 2019-20, Dr. Milanes led an effort to get residents and faculty in the Department of Family and Community Medicine trained in MAT, and she is one of 25 physicians nationwide who are working with the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) to create a pilot MAT curriculum. “Hopefully, by the end of the year we have a standardized curriculum that we can send out,” she says.

Second- and third-year residents in Family and Community Medicine have opportunities to engage with MAT patients by shadowing Dr. Khan at the rural clinic in Parlier, and they also can see patients in downtown Fresno who are being treated at the primary care clinic at Family Health Care Network.

The blend of rural and urban training experiences is unique, Dr. Khan says. “This problem is even worse in the rural areas and the training is even less available for those areas.” Providing addiction medicine in an underserved area is what attracted Dr. Khan to open the MAT clinic in Parlier this past August. After medical school, medical research and residency, Dr. Khan pursued further training in Global Health with the Health Equity, Action and Leadership (HEAL) Initiative with UC San Francisco. As part of his HEAL fellowship, he provided care on the Navajo Nation and in West Africa. “That was probably one of the most life-changing times in my life,” he says. “It really solidified what I wanted to do as my career, which is underserved care.”

Marlon Echaverry, MD, a third-year resident, has shadowed Dr. Khan. He has an interest in addiction medicine that he says comes from his father’s success in overcoming alcohol misuse when Dr. Echaverry was a teenager. “I know people can change.” He envisions a day when substance use is looked at as any chronic medical condition. “I hope for the day when it doesn’t have to be a specialty clinic and that every physician is trained in it,” he says. “I wish every (residency) program in the U.S. was doing MAT training and addiction medicine for their residents because then you would have an entire army of physicians trained in these therapies.”

Sireesha Mudunuri, DO, a third-year resident, is grateful for the opportunity to work with Dr. Khan at the MAT clinic at UHC in Parlier. “To actually see it in practice is very helpful,” she said. She expects the training will be put to good use after residency. “In talking to a lot of graduates, they have gone on to use it in their practices.”

MAT training is essential for the future physician workforce, but Dr. Khan can use help now. At the half-day MAT clinic in Parlier, he typically can see 10 to 15 patients. Most need to be seen every two to four weeks until they are stable, and each visit can take a long time. “If I have more than three or four new patients in a half-day, it becomes really difficult to complete all the work in a timely way,” he says.’

“I feel grateful to be a part of this, but also I know I cannot do this on my own,” Dr. Khan says. “So, when a resident is with me, it’s not only good learning for them it’s also helpful to me because sometimes they can help do additional history taking for the patients or follow ups with me that supports my work.”

Christine says everyone could benefit from primary care doctors being trained in MAT. She has transferred her primary care to Dr. Khan. “He got me set up for a mammogram, Pap. He got me set up for absolutely everything.”

Many of the patients with substance use disorder seen at the BRIDGE program at CRMC are patients in need of primary care physicians to oversee their care, Dr. Milanes says. “They need patient-centered care and chronic disease management.” UCSF Fresno’s goal is to provide those physicians through the training of residents in MAT and by augmenting substance use disorder and addiction medicine education for providers in the community, she says. “We want everyone to be on the same page as seeing this as a chronic disease and have an understanding of substance use disorder management strategies.”